Everything you wanted to know about the Chinese calendar but were too confused to ask

Although China today uses the Gregorian calendar for civil purposes, the traditional Chinese lunar calendar governs holidays—such as the Chinese New Year and Lantern Festival.

People all across China also use the traditional lunar calendar for selecting auspicious days for weddings, funerals, moving house, or starting a business.

China adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1912 but it was not widely used throughout the country until the Communist victory in 1949. This widespread change occurred on October 1, 1949, when Mao Zedong ordered that the year should be in accordance with the Gregorian calendar.

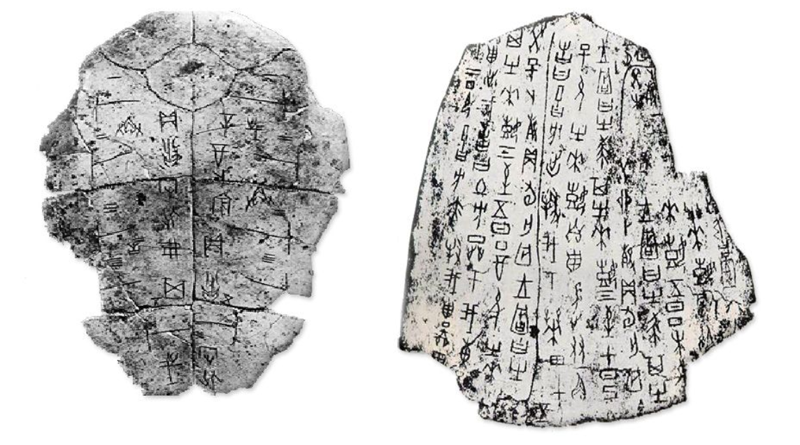

While the western calendar was first implemented by Julius Caesar in 46 B.C.E. and the Gregorian calendar (named after Pope Gregory XIII), was introduced in October 1582, the beginnings of the Chinese calendar can be traced back to the 14th century B.C.E.

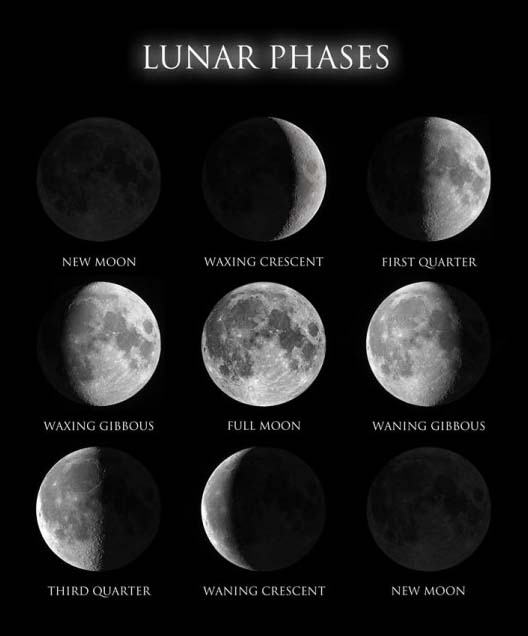

The Chinese calendar is a lunisolar calendar, which means it is based on exact astronomical observations of the sun and the phases of the moon.

The calendar uses moon cycles to mark the start of months, for years, a count of the sun and moon are used.

Before the Spring and Autumn period (approximately 771 to 476 BC), only solar calendars were used.

Different versions of the solar calendar are known to have existed

The five-elements calendar (五行曆; 五行历), a 365-day year was divided into five phases of 73 days.

The four-quarters calendar (四時八節曆; 四时八节历; ‘four sections, eight seasons calendar’, or 四分曆; 四分历), weeks were ten days long, with one month consisting of three weeks.

The balanced calendar (調曆; 调历), a year was 365.25 days, and a month was 29.5 days.

The first lunisolar calendar

The first lunisolar calendar was the Zhou calendar (周曆; 周历), introduced under the Zhou dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE).

Later, several competing lunisolar calendars were introduced, especially by states fighting Zhou control during the Warring States period.

The Chinese month & new moon cycle

The arrival of a new moon determines the first day of the month. In the lunar cycle, the new moon is when the surface is entirely dark (opposite to a full moon). During the month it grows from a crescent moon to full moon and back to the dark new moon.

The night of the new moon rising is regarded as the first day of the month. Regardless of what time it rises, the beginning of that day marks the start of the month. Let’s say for example the new moon rises at 8 pm, the entire day is the first day of the new month.

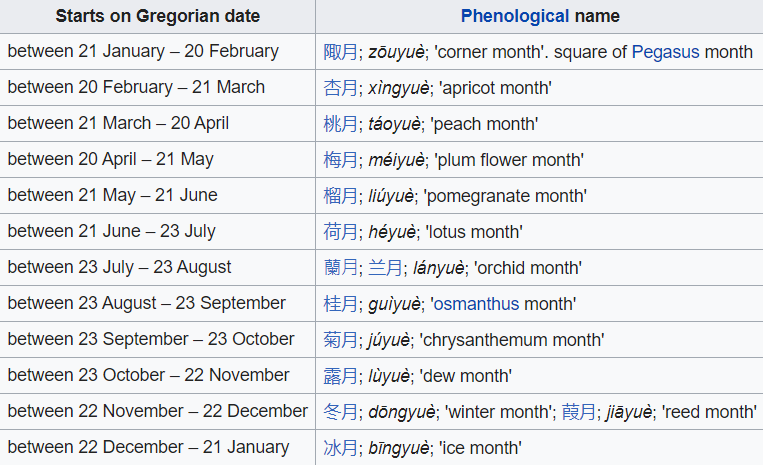

Lunar months in China were originally named according to natural phenomena

Months are defined by the time between new moons, which averages approximately 29 17⁄32 days.

There is no specified length of any particular Chinese month, so the first month could have 29 days (short month, 小月) in some years and 30 days (long month, 大月) in other years.

The 60-Year Cycle

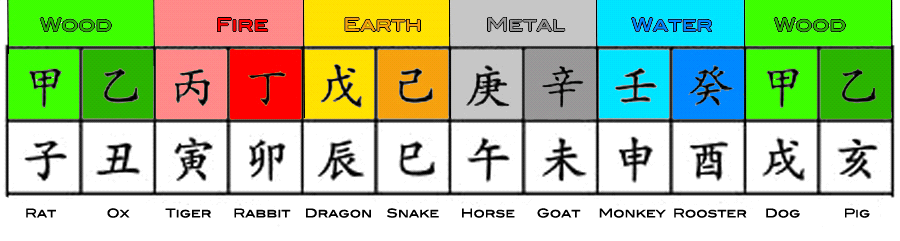

The Chinese Lunar calendar does not count years in an endless sequence. Each year is assigned a name consisting of two components within each 60-year cycle.

The first component is a celestial stem:

Jia (associated with growing wood),

Yi (associated with cut timber),

Bing (associated with natural fire),

Ding (associated with artificial fire),

Wu (associated with earth),

Ji (associated with earthenware),

Geng (associated with metal),

Xin (associated with wrought metal),

Ren (associated with running water),

Gui (associated with standing water).

The Chinese Zodiac

The second component features the names of animals in a zodiac cycle consisting of 12 animals:

Zi (Rat),

Chou (Ox),

Yin (Tiger),

Mao (Rabbit),

Chen (Dragon),

Si (Snake),

Wu (Horse),

Wei (Sheep),

Shen (Monkey),

You (Rooster),

Xu (Dog),

Hai (Boar/pig).

Each of the two components is used sequentially.

Therefore, the first year of the 60-year cycle becomes jia-zi, the second year is yi-chou, and so on. One starts from the beginning when the end of a component is reached.

The 10th year is gui-you, the 11th year is jia-xu (restarting the celestial stem) the 12th year is yi-hai, and the 13th year is bing-zi (restarting the celestial branch). Finally, the 60th year is gui-hai.

This pattern of naming years within a 60-year cycle dates back about 2000 years.

Calculating the Chinese New Year

Calculation of the Chinese New Year has a set of rules. However, as there are many exceptions things can get a bit confusing.

Generally speaking, the Chinese New Year falls between January 21st and February 21st. The precise date is the second new moon after the December solstice (December 21st).

Each year the date is pushed back by 10, 11, or even 12 days compared to the previous year, (with the lunar calendar, you’ll always know the phase of the moon based on the day of the month. but every year the lunar calendar is short by around 11 days).

This is always true unless the New Year falls outside the range of Jan 21st to Feb 21st.

If it does, a leap month is slotted in. In leap years, Chinese New Year day will instead jump 18, 19, or 20 days ahead to continue the pattern.

Dates of Chinese New Year from 1996 up until 2031.

Solar term

The solar year (歲; 岁; Suì), the time between winter solstices, is divided into 24 solar terms known as jié qì.

These solar terms mark both Western and Chinese seasons as well as equinoxes, solstices, and other Chinese events.

| Name | Marker | Event | Date |

| Lì chūn | 立春 | Beginning of spring | 4 February |

| Yǔ shuĭ | 雨水 | Rain water | 19 February |

| Jīng zhé | 惊蛰 | Waking of insects | 6 March |

| Chūn fēn | 春分 | March equinox | 21 March |

| Qīng míng | 清明 | Pure brightness | 5 April |

| Gŭ yŭ | 谷雨 | Grain rain | 20 April |

| Lì xià | 立夏 | Beginning of summer | 6 May |

| Xiǎo mǎn | 小满 | Grain full | 21 May |

| Máng zhòng | 芒种 | Grain in ear | 6 June |

| Xià zhì | 夏至 | June solstice | 22 June |

| Xiǎo shǔ | 小暑 | Slight heat | 7 July |

| Dà shǔ | 大暑 | Great heat | 23 July |

| Lì qiū | 立秋 | Beginning of autumn | 8 August |

| Chǔ shǔ | 处署 | Limit of heat | 23 August |

| Bái lù | 白露 | White dew | 8 September |

| Qiū fēn | 秋分 | September equinox | 23 September |

| Hán lù | 寒露 | Cold dew | 8 October |

| Shuāng jiàng | 霜降 | Descent of frost | 24 October |

| Lì dōng | 立冬 | Beginning of winter | 8 November |

| Xiăo xuě | 小雪 | Slight snow | 22 November |

| Dà xuě | 大雪 | Great snow | 7 December |

| Dōng zhì | 冬至 | December solstice | 22 December |

| Xiăo hán | 小寒 | Slight cold | 6 January |

| Dà hán | 大寒 | Great cold | 20 January |

Why was the calendar so important?

The calendar was important in ancient China because it was used by farmers to regulate their agricultural activities, and because regularity in the yearly cycle was a sign of a well-governed empire in which the ruler was able to maintain harmony between Heaven and Earth.

The calendar prepared each year by the emperor’s astronomers was a symbol that an emperor’s rule was sanctioned by Heaven.

According to Chinese legend, in 2254 B.C.E. the Emperor Yao ordered his astronomers to define the annual cycles of changing seasons, and during the Shang dynasty a calendar was prepared annually by a board of mathematicians under the direction of a minister of the imperial government.

Each new Chinese dynasty published a new official annual calendar, and publication of an unofficial calendar could be regarded an act of treason

Related article: Chinese scientists take ancient art of origami to the atomic level