There are 3 basic stages in the life of a typhoon, its origin (or source), the mature stage and the dissipation stage, where it dies out.

These occur in a continuous process, not as separate distinct stages.

Each stage may occur more than once during the life cycle of the typhoon.

As the typhoon develops, it may reach land and weaken before going back out to sea where it strengthens once more.

Typhoons are most likely to form in the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), where the North-East and South-East trade winds meet.

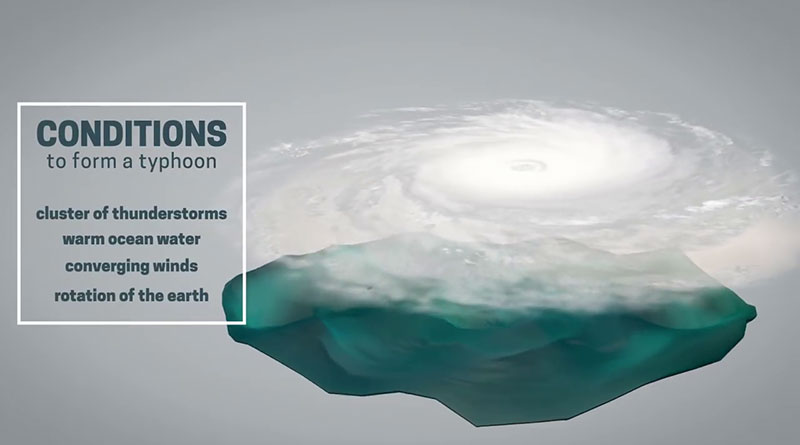

The formation of a typhoon depends on the following conditions coinciding.

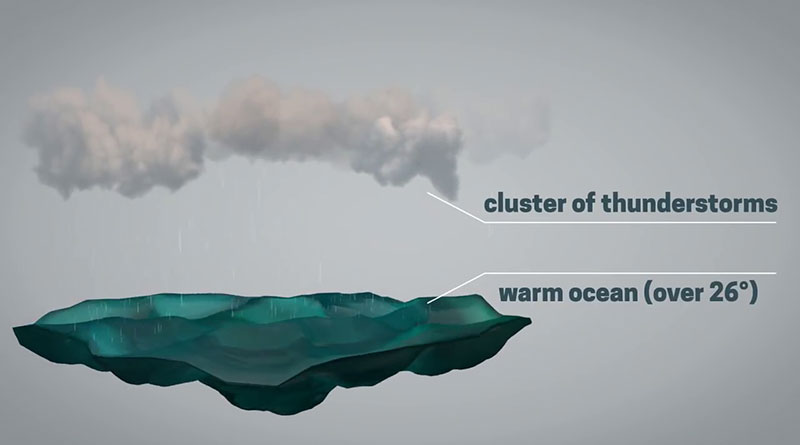

A large, still, warm ocean area with a surface temperature above 26.5 OC over an extended period of time.

This allows a body of warm air to develop above the ocean surface.

Low altitude winds are also needed to form a typhoon.

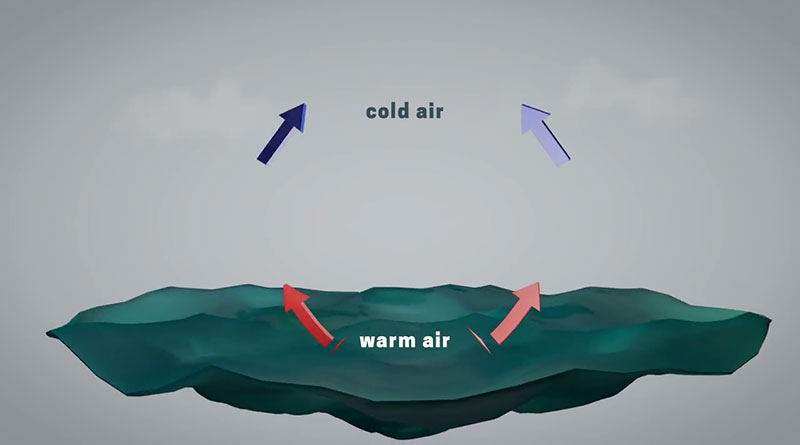

As air warms over the ocean, it expands, becomes lighter and rises. Other local winds blow in to replace the air that has risen, which in turn warms and also rises. The rising air contains a huge amount of moisture evaporated from the ocean surface.

As it rises the air cools, and the moisture condenses to form huge clouds about 10 km up in the troposphere.

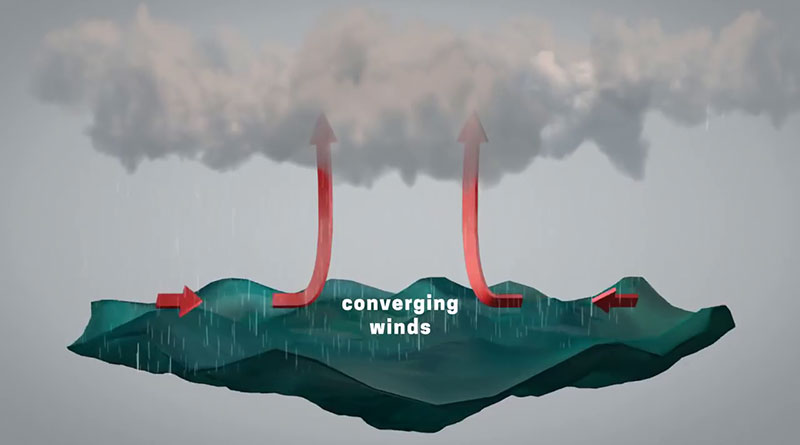

More warm air rushes in and rises, drawn in by the draft above. The rising drafts of air carry moisture high into the atmosphere which causes the clouds to become very thick and heavy.

Condensation then releases the latent heat energy stored in the water vapour, providing the typhoon with more power. This creates a self-sustaining heat cycle.

Drawn further up into the atmosphere by the release of energy, the clouds can grow up to 12 – 15 km high.

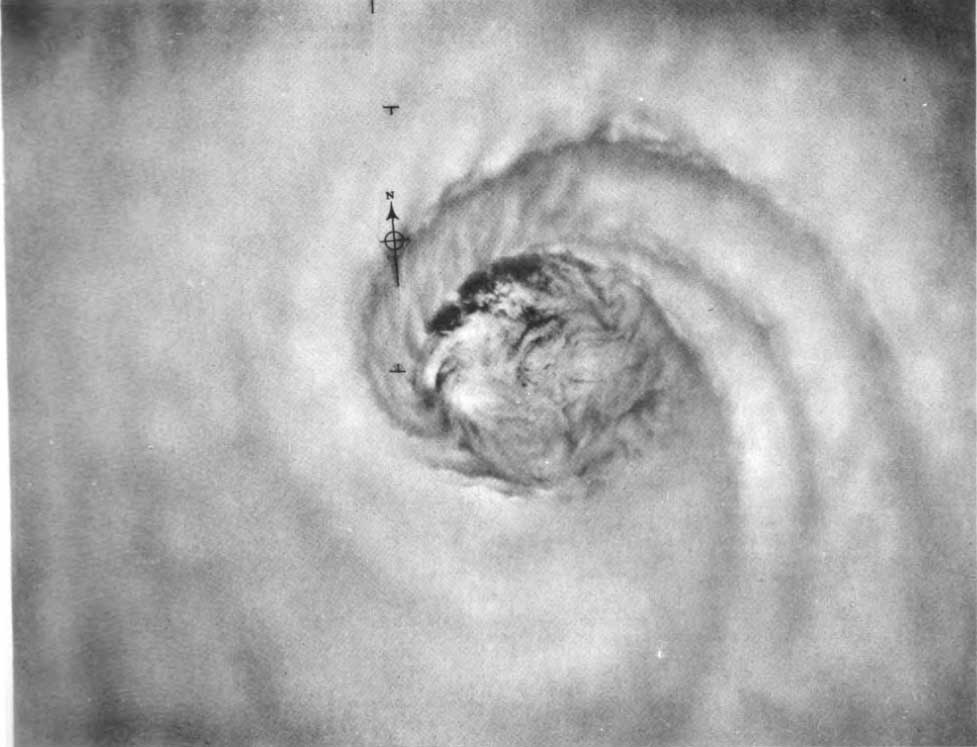

The force created by the earth’s rotation on a tilted axis, (the Coriolis Effect), causes rising currents of air to spiral around the centre of the typhoon. It’s at this stage that the typhoon matures, and the eye of the storm is created.

As the air rises and cools, some of the dense air descends to form the clear still eye as the typhoon rages around it.

The eye wall where the wind is strongest behaves like a whirling cylinder, (typhoons rotate anti-clockwise in the northern hemisphere).

The lowest air pressure in a typhoon is always found in the centre and is typically 950 millibars or less. The average air pressure at the earth’s surface is 1010 millibars, which means that typhoons have significantly lower air pressure than the air that surrounds them.

The bigger the pressure difference, the stronger the wind force.

One of the lowest air pressures ever recorded was 877 millibars for typhoon Ida, which hit the Philippians in 1958 with wind speeds that reached 300 Km/h and resulted in 1,269 fatalities.

Once formed, the typhoon’s path or track follows a course driven by global wind circulation.

As warm ocean water feeds it heat and moisture the typhoon usually continues to enlarge.

When a typhoon passes over land or cold water, the basic fuel (warm ocean water) that drives the storm is cut off. Passing over land will quickly weaken the storm (not because of friction as some believe, but because of the loss of the warm moisture).

Related article: Typhoon Maqi 1973 – A reflection on one of the strongest & deadliest typhoons to hit Hainan